Cultural festivals are a common thing in a melting pot like the United States. The act of showcasing the best, most colorful, fun, delicious and awe-inspiring traditions of one's culture has long proven a draw.

But not every cultural display is as open to active participation as the one that happens at the Cuyahoga County Fairgrounds in Berea every summer.

The Ohio Scottish Games and Celtic Festival features highland games (also known as heavy athletics), solo bagpipe and band competitions, as well as displays from 20 bands, more than 20 clans, 60 vendors, 130 dancers, medieval reenactment, full contact jousting, darts, pubs, artists and a wild array of animals from Ireland and Scotland. The event is in it's 48th year, and fourth in Berea.

Tyler Tagliaferro is the chairman of the Scottish American Cultural Society of Ohio which puts on the festival.

"This is the only Scottish games for Ohio," said Tagliaferro. "There are two separate bands that drove up from Cincinnati. There are two bands that drove from Columbus. We are pulling from Toledo as well as Youngstown."

Heavy athletes

One of the people who has long been a mainstay at these games is Doug Steiger, a retired fireman and track coach from North Royalton.

"When I grew up, I'd been to the Ohio games as a kid many times. Years ago I just said, 'I'd like to try that,'" said Steiger.

Steiger's mother, Betty Steiger, was born and raised in Scotland and introduced Doug to the sport when he was young. But it's not something she brought with her when she came to the United States as a teenager.

"Never saw that in Scotland," said Steiger of the sport. "At first I thought, well this is men in a lot of kilts and stuff, and I like that ... I couldn't stop coming back, so every year I've been back since."

Heavy Athletics, or highland games as they’re sometimes called, involve an array of lifting and throwing events. Among the events are the stone put, which involves throwing smooth stones weighing over 20 pounds; sheaf toss, which simulates the tossing of a sheaf of wheat for height; and the most popular and well-known event of the bunch, the caber toss, which sees competitors flipping what can be accurately described as a "wee telephone pole" end over end in the hopes of perfect straight accuracy.

Doug Steiger has achieved the highest levels of success in Highland Games, and it has taken him all over.

"I've been to games in California, Washington, Colorado, up the East Coast, Florida. I've competed basically in probably half the states," said Steiger.

His mother Betty is now 82 and comes out with her grandchildren to watch her son compete. Now, Doug is not just a long-time competitor but a coach to many others.

Jake Mantle is one of the many athletes who came up under Steiger.

"I got started in it because of Doug. He was my high school throwing coach. We talked about it for years as I was growing up," said Mantle.

He competed in track and football throughout high school and college and was looking for a way to stay active after graduation, and came back to his old coach for training.

Mantle now competes in the advanced Men's A division at the games, and finished 4th overall this year. While Mantle has Irish heritage, athletes of all backgrounds are drawn to the events.

Visitors to the culture

Neil Kalanish trained with Steiger, Mantle and a group of other athletes ahead of the game this year. Kalanish has no Scottish or Irish heritage at all.

"This is my first time ever getting involved with this. I train with my buddy over there," says Kalanish, gesturing to his friend. "We did a lot of strongman and powerlifting stuff, and we saw this come up, and we're like, 'Hey, let's all jump in and try something new out.'"

Highland games are more of a product of the diaspora these days, put on by people who are generally more distantly connected to Scotland than the Steigers, and enjoyed and participated in by people with no connection at all.

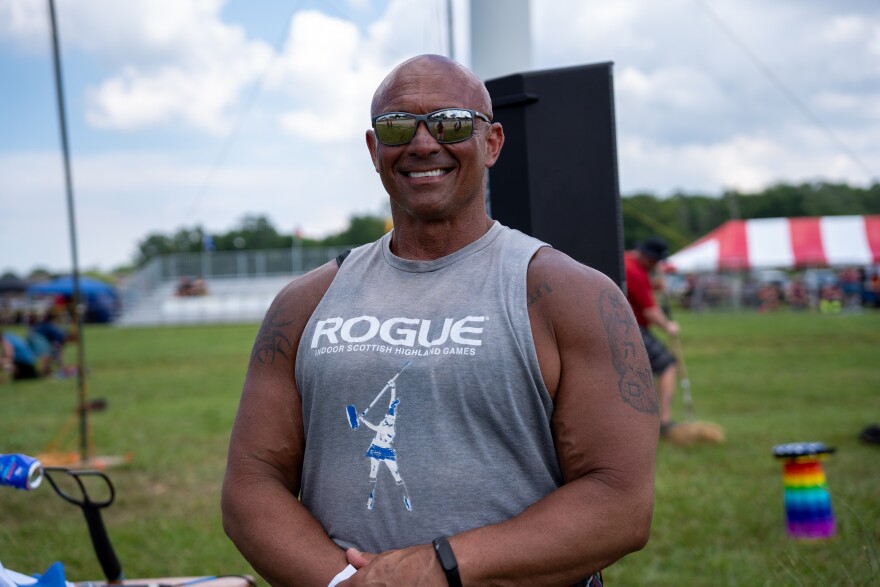

Kerry Overfelt is a former professional champion of highland games who is close with Doug Steiger and was on hand to emcee the events. He's Cherokee and German without a trace of Scottish roots.

"That's the beauty of this sport. You do not have to be Scottish to participate," said Overfelt. "You are more than welcomed in. You're gonna see a lot of camaraderie between all of the competitors out here."

Betty Steiger herself came to this country for a similar quest of belonging in a foreign culture.

"The reason I came to America was because I wanted to see Elvis and get married to him," said Steiger.

The games' chairman, Tyler Tagliaferro, is himself half-Italian and half-Irish, but nonetheless a great lover of the signature Scottish instrument, the bagpipes, whose voices ring out in cacophony on the day of the festival.

"The bagpipes specifically are an instrument that can't be put in a corner. They're evocative. When you hear them they're going to make you feel something," said Tagliaferro. "Although they originate from Scotland, not being Scottish, I heard them and I thought, 'I want to do that,' and I think so many people feel the same way."

Another outsider who fell in love with the pipes is Laura Romine. Her sister lives in Springfield and Romine traveled from Jacksonville, Florida, to compete in the solo bagpipe competitions, which she described as one of the big competitive events in the country. Romine has always felt comfortable and accepted in the bagpiping community despite having no Scottish or Irish heritage.

"Anyone who takes up the instrument becomes Scottish. Anyone can do it," said Romine.

That assertion was backed by Scotsman, Jeff Craig. He came up to compete with his group, the Cincinnati Caledonian Pipes and Drums band.

"I think being in the pipe band, it's a musical ensemble, and I think musicians are just more open to that passion that people have. If you've got the passion and the dedication, you are welcome to be part of it," said Craig.

Twilight tattoo

As the day winds down, attendees marvel at the feats of strength and lung power and gather in the center of the fairgrounds for the twilight tattoo. The common spectacle at Scottish festivals, also known as the massed band. Over 400 pipers and drummers, all the ones who came to compete against each other this day, march together and play as one. Surrounded by attendees and accompanied by some highland dancers, the bands marched in unison under the direction of drum major, Jim Engle.

On a day where diverse voices have been mingling in their own circles, it’s a perfect way to end things, with everyone together on one field, basking in the sounds of tradition.

Jeremiah Geisinger is a mead brewer from Massillon with Scottish roots who was at the event, in his kilt. He summed up the reason so many people come out for the festival.

"I think it makes the ancestors happy."